What is intelligence?

Sometimes people think I’m intelligent. I’m not really, I’m just academic, bloody-minded and like to use semi-colons. And to prove I’m not that smart, I’m going to write a mini essay, because that’s the only way I’m able to think1.

Intelligence is broader than academic ability

So what is intelligence, anyway? Let’s kick off with the fabulous Rose Luckin, who thinks about this as part of her work in AI. Take a look at her Turing Lecture where she discusses intelligence not as a series of different intelligences, but as a complex interwoven set of elements. It’s about 8 minutes, from 19’35”-27’30”. Go on.

You didn’t watch it, did you? Fine, I’ll summarise.

Her research suggests that intelligence includes these elements:

- Interdisciplinary academic intelligence – the ‘standard’ definition of intelligence, but notice that she focusses on interdisciplinarity, because the answers to 21st century problems aren’t held by one discipline any more

- Meta-knowing intelligence: this is thinking about and understanding knowledge. What is knowledge? Where does it come from? Why should be believe what we hear?

- Social intelligence: we do much of our learning and problem-solving through social interaction

- Meta-cognitive intelligence: understanding our thought processes, such as noticing when we’re distracted, having an accurate picture of what we do and don’t know, or whether we’re learning effectively

- Meta-subjective intelligence: reflecting on how well we’re developing emotional intelligence

- Meta-contextual intelligence: our ability to move into and out of different contexts, places, online/offline. She describes this as the most underestimated element of intelligence

- Perceived self-efficacy: this brings together all of the other elements, and includes goal setting, motivation, managing our learning, and so on.

So, universities teach you academic intelligence, although not very interdiciplinarily; a bit of meta-knowing; a bit of self-efficacy; but how much you learn of the rest of these elements is highly variable by institution. So a university degree or two, or being naturally academic, isn’t representative of a rounded intelligence.

So where next? Oh look, it’s Sir Ken Robinson again:

“I like university professors, but you know, we shouldn’t hold them up as the high-water mark of all human achievement. They’re just a form of life, another form of life. But they’re rather curious, and I say this out of affection for them. There’s something curious about professors in my experience — not all of them, but typically — they live in their heads. They live up there, and slightly to one side. They’re disembodied, you know, in a kind of literal way. They look upon their body as a form of transport for their heads, don’t they? It’s a way of getting their head to meetings.”

“[intelligence is] diverse. We think about the world in all the ways that we experience it. We think visually, we think in sound, we think kinaesthetically. We think in abstract terms, we think in movement. Secondly, intelligence is dynamic…the brain isn’t divided into compartments. In fact, creativity – which I define as the process of having original ideas that have value – more often than not comes about through the interaction of different disciplinary ways of seeing things.”

Intelligence is context dependant

Next, Oliver Burkeman, whom I adore. If I could have written anyone’s back catalogue of articles, it would be his. For example, this article on the importance of empathy in combatting bigotry or how being a moderate is a strength are towering examples of good thinking in a much shorter word count than I ever manage.

Burkeman once wrote (in an article that despite my best Google-fu and going 50 pages into his article index in the Guardian, I haven’t been able to find to link to) that intelligence is situational (Luckin’s meta-contextual intelligence): that here in this professor-worshipping world, accumulating different pieces of paper is what we value; however, in a survival situation where we need to know what roots we can eat without dying, that hypothetical professor is less than useless.

I’ve been very lucky in that I’ve been able to choose my context, meaning I can choose one that fosters and appreciates the kind of skills and intelligence I value. I have lots of thoughts about what intelligence is not because I’m ‘smart’, but because this has been an interesting topic to me for years, because I have a job that means I have to think about knowledge, and because I spend a lot of time with researchers. Prolonged exposure to the ways intelligent people think means that I picked up their ways of thinking too.

Aha, an opportunity to quote Terry Pratchett! By which I mean an opportunity to quote Terry Pratchett that I could take advantage of if only I could find the quote I wanted! 2

I think it was in one of the books about Unseen University: that the wizards calibrated their idea of what was normal from the other wizards around them – but because they were all strange, everyone at the university just got weirder and weirder.

The Verb Ninja trying to remember a Terry Pratchett quote

Alongside ‘normal’, I believe that ‘intelligence’ and ‘stupidity’ are contagious – you catch it from the people around you.

Intelligence is a habit

I was brought up to think. I was brought up to treat my brain as a crowbar, inserting it into cracks in the world and levering until the metaphor falls to pieces 3. And this taps into meta-knowing intelligence (thinking about and understanding knowledge) and meta-cognitive intelligence (understanding our own thought processes). My whole family does this: when we meet a new idea, we take a step back and reflect. Where did this ‘fact’ come from? How is it context-dependant? Why should we believe it? How does this fit into my view of the world? How might I be biased? And so on, and so on. But this isn’t about innate intelligence – it’s all about practising until this becomes your first reaction to new information.

Being academic is more perspiration than inspiration

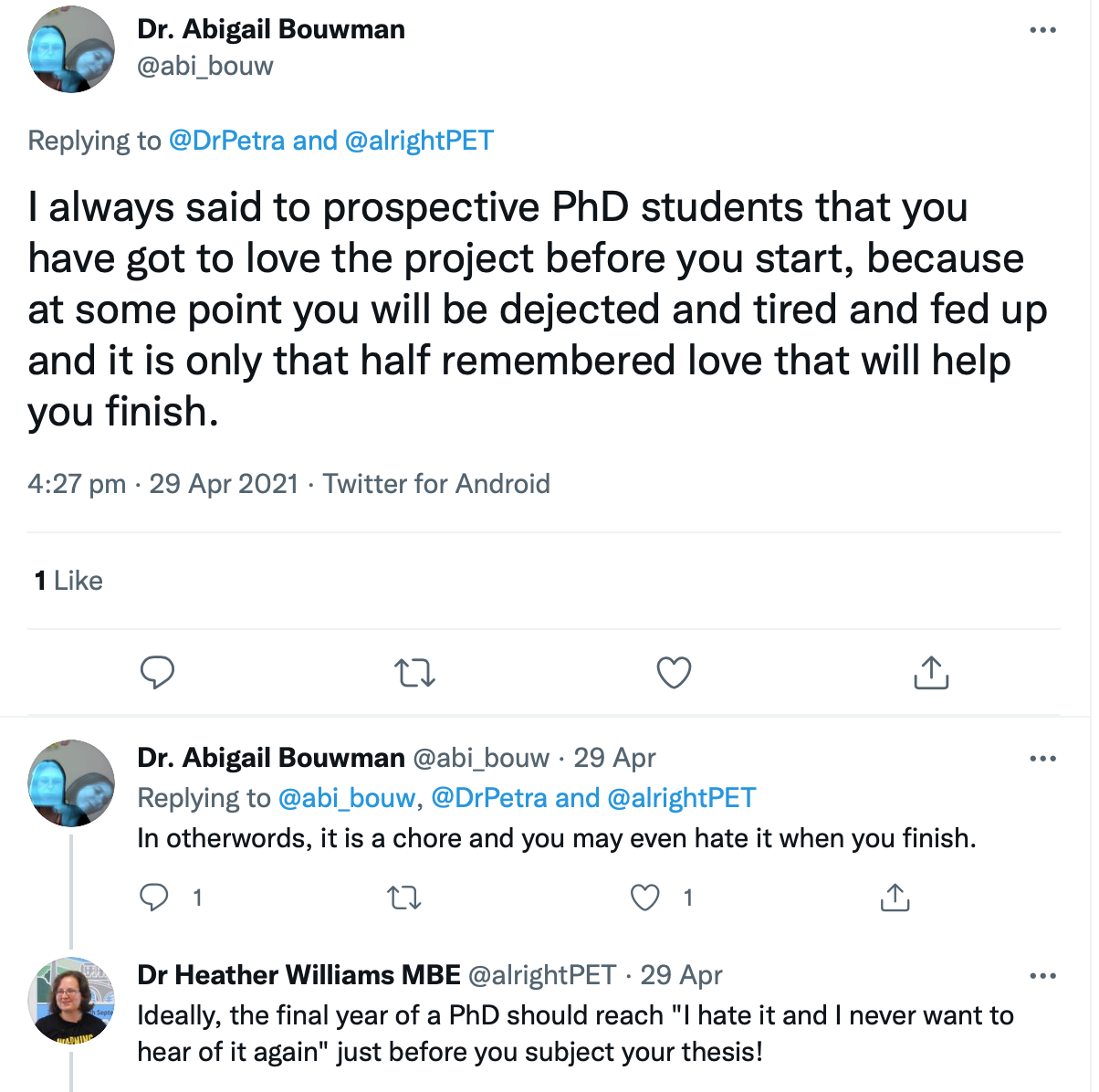

Finally, I described myself earlier as academic and bloody-minded, and the more time I spend in academia the more I realise the importance of that second one.

So, in conclusion, I’m not that smart, I’m just lucky to value the same type of intelligence as wider society, very deliberate about the contexts I move in and who I spend time with, and determined to think even when it’s really annoying (and sometimes when it’s self-destructive). But if you ask me to argue without preparation or formulate a viewpoint without others to bounce ideas off, I’ll need a bit of a sit-down. I have to actively switch on emotional-intelligence mode, I hate working in a group, and in certain contexts I’ll always be the weird one in the corner copy-editing the pub menu.

My lovely friend, however, as well as having a degree, is creative, compassionate, reflective, and smarter than most of the people around her. It’s no contest, really.

-

I.e. I can only think by pontificating to others – in case you needed evidence that I’m academic. ↩

-

Seriously, I wrote 95% of this blog post a month ago, and have spent the time since re-reading Pratchett to try to find the quote. It’s been a good month. ↩

-

It’s only recently that I’ve realised that MAXIMUM THINKING isn’t always the right choice for mental health. Don’t think too much, kids – you’ll regret it later in life. ↩